Managing multi-asset strategies integrates a broad spectrum of inputs, from macroeconomic trends to market developments. It also involves combining a range of underlying building blocks, which help a given strategy achieve its desired outcome.

US exposure across asset classes form a key part of this process, and we believe that there’s support for them to remain relatively attractive versus other developed markets, even as some investors wonder whether their leadership will fade. We expect this to be driven by several important secular trends that, we believe, will alter the global macro landscape.

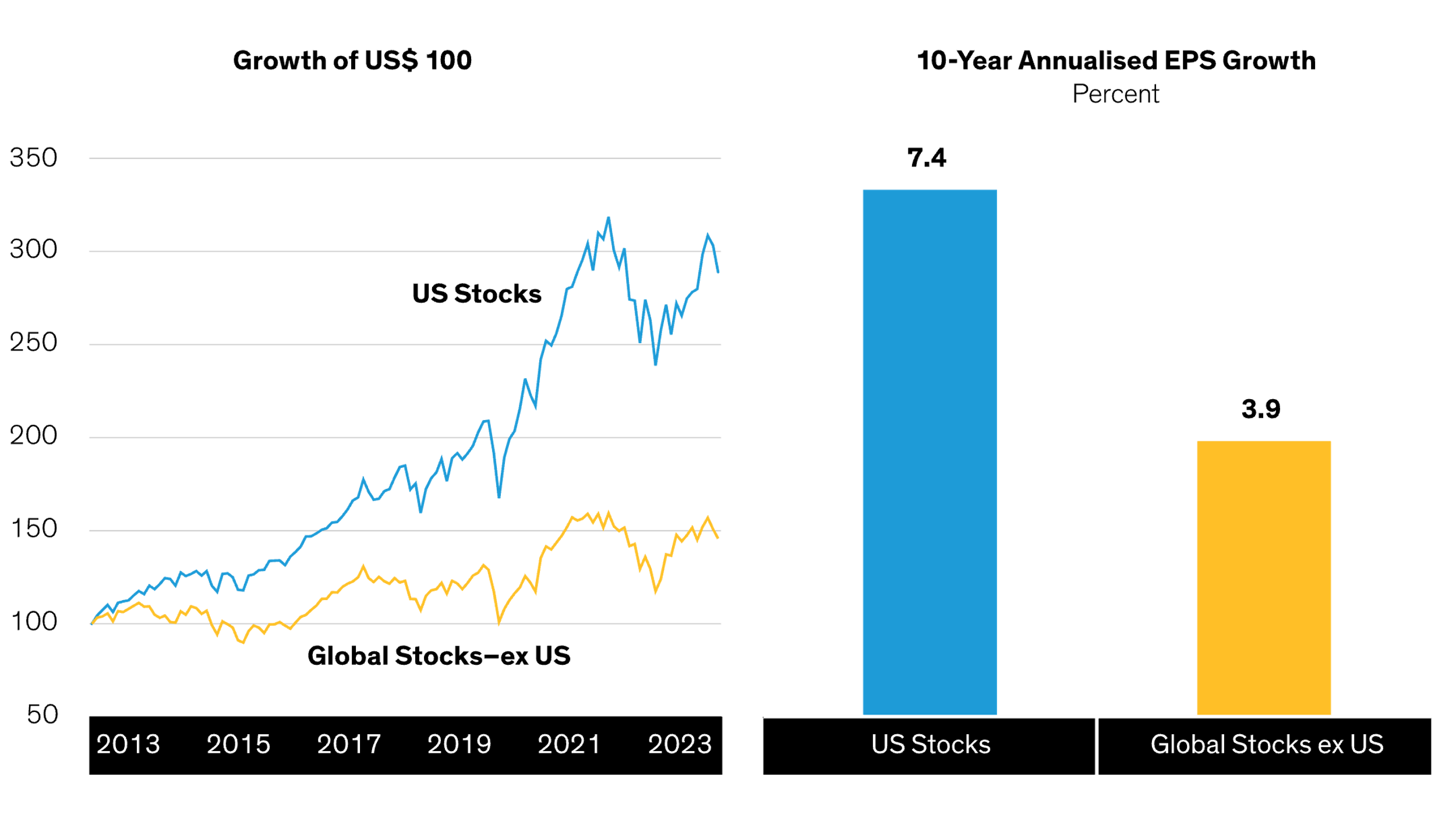

Since 2013, US stocks have outperformed other developed markets by about 7% on an annualized basis, which would have nearly doubled the ending value of an initial investment by September 2023 (Display left). Behind this momentum was consistently solid earnings growth, nearly twice that of non-US companies (Display right).

The contrast is even sharper for growth stocks, which include many US-based tech leaders. In fact, US growth equities, represented by the MSCI USA Growth Index, outpaced the MSCI World ex USA benchmark by almost 10% annualized for the 10-year period. Year to date through the end of September, the US advantage for US growth stocks was 21%.

US Equities Have Outperformed and Outearned

Despite the strong showing, some investors may question whether the US leadership trend will reverse course—but we’re optimistic.

We see four megatrends in particular influencing how companies will operate and compete in the next decade, and expect many to make the US attractive compared to other developed markets.

These secular trends include changing demographics, deglobalization and climate change. Right alongside them is the ongoing digital revolution and explosion of artificial intelligence (AI), of which we expect the US to be a key beneficiary.

Most of the US equity market’s recent outperformance is tied to the excitement around AI’s growing penetration across industries which we think will drive secular growth for years. As greater spending on AI and other next-generation initiatives benefit technology, US equities should become relatively appealing overall, given that the US market is more heavily tilted towards tech companies (Display).

The world population is getting older on average, the result of falling birth rates and longer life expectancies just about everywhere. It’s now likely that the number of working-age people in developed-market economies has likely peaked and will steadily decline in the coming decades.

Fewer workers, a challenge that seems more acute in China than in the West, strongly implies a decline in real economic growth, unless there’s a sustained increase in productivity by other means. AI may help, but it’s not yet a practical solution.

Increasing the labor-force participation rate among older workers could help offset overall workforce shrinkage. This trend is underway in the US, where the participation rate of those 65 and older is already 24%, higher than that of most developed countries. China’s rate for the age 65–79 cohort is just over 20%. If it stays in that range, the baseline scenario still shows a prolonged decline in the working-age population ahead, along with lower productivity and slower economic growth.

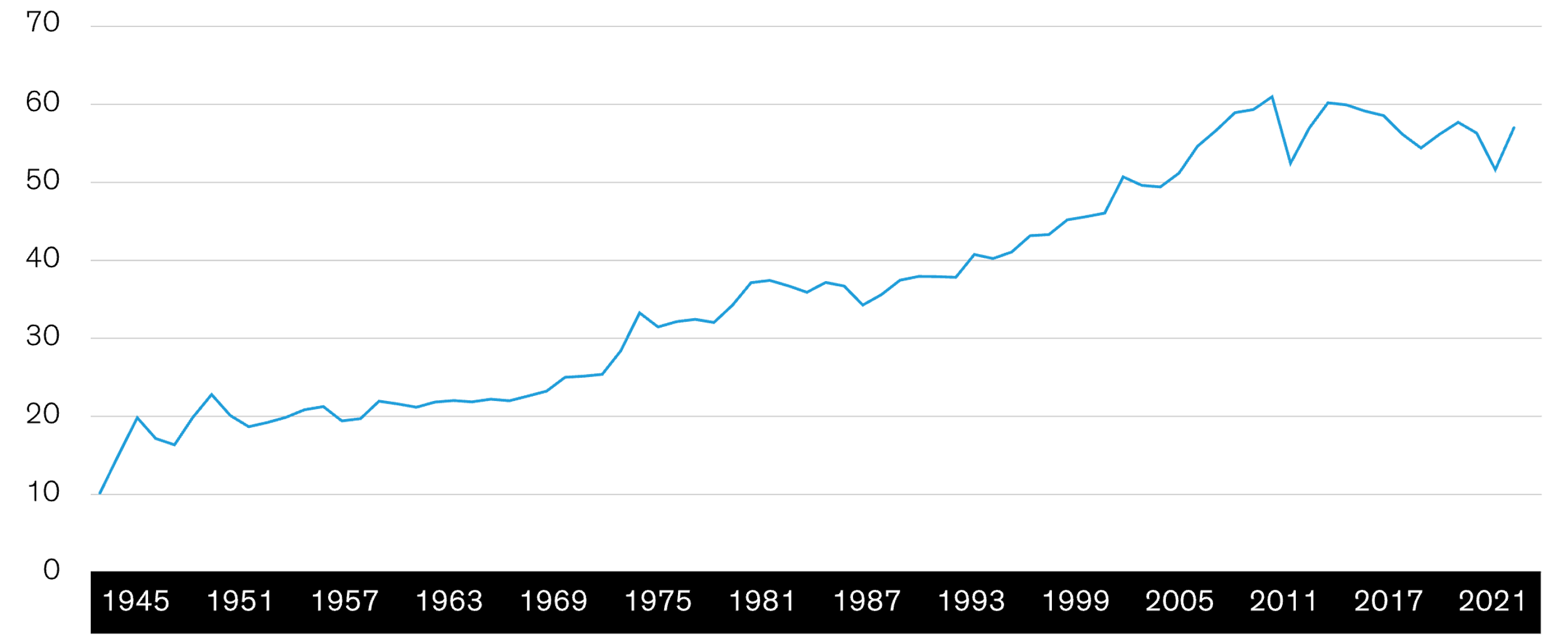

Globalization rose rapidly after World War II, as measured by world trade as a share of global gross domestic product (GDP). It really accelerated between 1980 and the 2000s, as China opened its markets, more large firms leveraged offshore labor and new technology improved the reach and scale of successful firms. But globalization has been in gentle retreat for about the last 10 years (Display).

Deglobalization impairs economic growth by reducing trade and addressable markets, though it’s difficult to forecast its scale. Certain trade-dependent nations could be more at risk, but the US economy could be large enough to absorb some amount of shock.

Germany, for example, could face significant headwinds, given its reliance on Russia for energy, China for exports and the US for a defense umbrella. Meanwhile, the US has become self-sufficient in key commodities, and has one of the most robust demographic profiles among developed nations. “Reshoring,” or bringing supply chains back in-country, has been effective so far, thanks in part to fiscal policies. In fact, US manufacturing CFOs are more likely to relocate their supply chains to the US than anywhere else, according to one survey.*

While the Paris Agreement focused global commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit temperature increases in this century to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, forecasting the effects of climate change on economic growth is harder to pin down. There are multiple effects and linkages, such as rising temperatures and sea levels, more extreme weather events, potential loss of habitats and biodiversity, conflicts over resources and pressure on migration. All these will likely vary significantly across regions.

Among regions, the greatest burden will likely be felt by emerging markets, which provide both the biggest supply of, and demand for, natural resources. They’re also most likely to feel the physical effects of rising baseline temperatures and have the least capacity to cope with climate variability and extremes. Among developed nations, the differences are likely to be more modest. In Europe, production is likely to rise with temperatures, while North America may experience a moderate decline in production, as measured by national output. That said, the US is among the world’s largest spenders on clean energy, bolstered by provisions in the recent Inflation Reduction Act–which creates numerous investment opportunities.

The four secular forces we’ve described will likely create headwinds and opportunities as they reshape the global economic and investing landscape and have meaningful bearing on inflation, growth, and market volatility. That could have significant implications for asset-class return patterns and interrelationships as well as greater returns dispersion across the global markets.

In most environments, there’s usually potential for risk assets to deliver positive real returns over time, especially if positioning remains broad. Stocks serve as a multi-asset strategy’s anchor position for growth, and firms that deliver sustainable earnings growth should be rewarded. In our view, many of these will be US-based companies, and the role of US stocks in multi-asset strategies’ equity allocations shouldn’t be underestimated.

Of course risk assets like equities or high yield credit should be accompanied by diversifiers and other return sources that can adapt as conditions change. For example, with yields likely to stay higher for longer, bonds are a strong income source and diversifier. As always, multi-asset investors should stand ready to refine the mix as conditions continue to evolve.

Other News